“Shalom Uveracha”: How Did People Really Speak in Israel 100 Years Ago?

- The UAB Team

- Jul 8, 2025

- 4 min read

A new project by the Academy of the Hebrew Language seeks to trace the evolution of Hebrew expression during the revival period of the language, using personal texts from the early 20th century. The results reveal trends that prevailed both then and now and offer a glimpse into everyday life in the Yishuv.

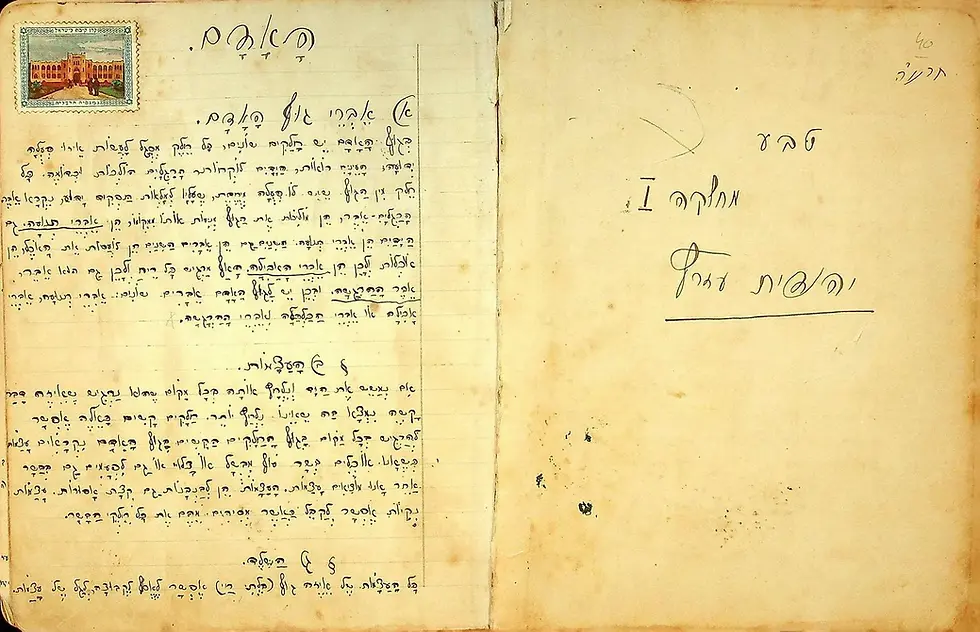

In 1930, Sarah Marcus left the Land of Israel on a mission to Iraq. Marcus, who had immigrated from Poland, was sent to Baghdad to teach Hebrew to Jewish girls at the “Shemesh” school. The journal she kept at the time, when she was just 22, was recently handed over to the Academy by her granddaughter, as part of the new project Hebrew from the Past. The initiative aims to collect personal Hebrew-language texts—letters, journals, and notebooks from the early 1900s—in order to understand how modern Hebrew was expressed during its formative years.

“We’ve all heard the name Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. We all learned the historical narrative of the Hebrew revival. But do we know how the new Hebrew actually sounded in the mouths of its first speakers at the start of the 20th century? How did they really speak? How did they sound during recess? What words did they use in the grocery store? How similar was their Hebrew to ours?” asks Dr. Ruth Stern of the Academy.

One example: a nature notebook found in a trash bin. “Many of these texts have vanished over the years, and it’s important to preserve the few that remain,” Stern says.

Marcus’s personal diary stands out: in it, she shares candid thoughts about love, friendships, and work. Beyond the content, the linguistic level is impressive (original spelling preserved):“הלב גדוש התמרמרות והמוח צר מהכיל את המון המחשבות… אחת מסבכת את חברתה ואיני יודעת איך להיחלץ מהמצוקה ולהשתחרר מהלחץ המעיק על הלב”She adds:“אל נא יראו דברי כמליצות… לא פעם סבלתי ולא פעמים נטפה עיני דמעה. אך תמיד השתדלתי לגרש את הרוחות הרעות מעל פני. לא רציתי לעשות את דירתם קבע בלבי.”

In another entry:“ביחס לחבת בחור אינני עקבית. הוא מתחבב מהר וחיש נמאס עלי… אחרי שאני רוכשת את לבם שוב אין להם כל נגישה אל לבי… הלאה ההשליות! אסור לערג ולהאמין באפשרות הדברים שאליהם משתוקקים. צריכים לדכא את התשוקות ולחכות בסבלנות לאשר ילד יום… אין ברצוני להאריך את הדבור על מהות התקוה וערכה. חוששני כי אגרר אחרי הפסימיזם.”

Most of those who spoke Hebrew at the time had learned it as a second language. “It wasn’t spoken in their homes,” Stern notes, “yet they achieved remarkably high levels of fluency. I wish I could write like that.”

“We Sat, Ate, and Shavnu”

The project also collected other types of texts: a wedding invitation, a science and nature notebook from a student at Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium (found in the trash), and dozens of letters written in 1928 by third-grade students in Zichron Yaakov to their teacher Rachel Stacher while she was on leave.

Stern calls the children's letters “a real treasure for linguistic research.” First, because many of the children were native Hebrew speakers educated in Hebrew schools, their language gives a direct look into common expressions of the time. Second, the letters are virtually unedited, full of spelling mistakes and authentic language use.

Despite the errors, the letters remind us: kids are always kids. One letter tells of misbehavior in class:“שבתי התנהג לפני המר. וגם בא אלנו תלמיד חדש ושמו משה שבבו. אככך אברהם בא מאחורי החלון וצעק כו כו קרקו.”

“These letters let us peek into the linguistic world of early native Hebrew speakers,” says Stern. “Because children write the way they speak—more or less—we can learn from their letters how they talked.”

Even so-called “mistakes” are invaluable data. For example, one student wrote:“באז ישבנו בחורשה על יד בית חרושת של סחוחייות. שם ישבנו ואכלנו ושבנו.”He meant: ואז, זכוכיות, ושבענו. Much like some today say ספתא instead of סבתא, this kid wrote סחוחית.

Another child wrote:“המורה אמר שאני אציר ציור יפה והוא יעשה מזגרת ויתלע את זה על הקיר.”Instead of מסגרת and יתלה – showing phonetic patterns still seen today.

Some letters reveal confusion about future tense or infinitives:“יותר אן לי מה לקתב”,“שתקתבי עד מכתבים”,based on forms like כתב → יכתוב and לכתוב, all with dagesh (emphasis) in the כ.

There are also creative variations on ו' החיבור (the conjunction “and”), e.g.“שלום אוברכה”,“אמי ילדה ילדה אושמה רות”,“ואוביחוד דוד”.These might reflect pronunciation norms of the time.

Rachel Stacher passed away in 1975. Earlier this year, her granddaughter and the director of the Zichron Yaakov archive unveiled a plaque in her memory outside her former home. The archive also holds a photo of Rachel with her students—some of whose letters are at the heart of this research. The Academy would love to locate their descendants.

A New Linguistic System

Just a few decades before these letters were written, Hebrew was mainly a written language. But during this time of major cultural transformation, it became a spoken—and even native—language in the Land of Israel.

“When we talk about the revival of Hebrew, most people think of new words coined to fit modern life,” says Stern. “But vocabulary is just the tip of the iceberg. What emerged was an entirely new linguistic system: grammar, syntax, pronunciation, conversation habits, and writing styles—all of which had never existed in this form.”

This system, she stresses, “wasn’t created in a lab.” It grew through daily use—on the streets, at home, in class. Unlike the formal pronunciation of official recordings, this Hebrew was everyday speech, with its quirks and variations.

For example, in early 20th-century speech, people would say:“אני קוראת” (with the stress pattern of שומעת),“אני יוכלה”,and “שבוע העבר” instead of “שבוע שעבר”.

Unlike many linguists who lament modern-day Hebrew, Stern sees continuity:“People say Hebrew today is deteriorating, that it used to be better. But these letters prove otherwise. The same linguistic patterns existed then. We’re not degenerating—we’re evolving.”

And the reason mistakes sound familiar today? Because they follow natural linguistic logic:“If we say ‘אני כתבתי’, why not ‘את תכתבי’ with a dagesh?”

Comments